Four Hundred Loons

Four Hundred Loons

by Paul Randolph Spitzer, PhD

(November 5, 2014)

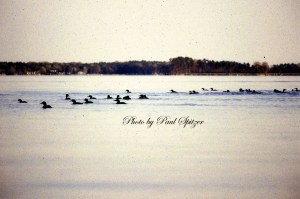

November brings migratory waterfowl from the North Country to the Bay. Among these are the loons, well-named in the UK as Great Northern Divers. They are the size of a goose, and are very partial to the Bay’s annual crop of “peanut” menhaden—nurtured on plankton in countless creeks over the warm summer.

These fish are now about 5 inches long, and already they form dense schools. Soon they will migrate from the Bay to warmer ocean waters, some swimming as far south as the Carolinas. The newly arrived loons practice an “intercept fishery” on the peanuts, forming noisy cooperative flocks in the lower reaches of some Bay tributaries. They form a live fishing net, most of them underwater at any given time, surfacing only to gulp air for a second then rejoin the pursuit. The water is dense with plankton, and the diving loons often push their prey toward the surface for easier visibility. Gulls know all about this, and several species hover to take fish at the surface, benefiting from the loons’ expertise.

After a while, the loons surface to breathe and digest. Then one realizes that what looked like a dozen loons is actually a flock ranging from 30 to 80 birds. I say “birds” advisedly, because loons are very unbirdlike birds. They live entirely on the water, alternating from northern ponds in summer to the open sea in winter—where the molting adults replace their wing feathers and go flightless. That flightless wingmolt period of several weeks is a measure of what tough marine animals they are. In that winter season, many disperse over the continental shelves of the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, with a deep-diving capacity similar to marine mammals.

Loons begin to breed at ages 5–10, and fledge at most 1 or 2 young each year. Although complete water masters, they are helpless on land, and their heavy-bodied flapping flight is a demanding aerobic exercise—thus their preference for cool water and air. On an autumn Chesapeake calm, mostly you will see them swim in to join a feeding-flock. Such a flock cues other loons with a musical chortle of feeding calls. I hear them from over a mile away, and I assume loons have much keener hearing than I do.

So, what you behold is cooperative predation tactics by highly intelligent, long-lived water masters who understand their annual autumn Chesapeake Stopover. HOWEVER: For this to work, the peanut menhaden prey base must be abundant, and that has been deficient for 20 years. Since the early 1990s, older menhaden were overfished under flawed NMFS models. The big musical autumn loon flocks I had enjoyed prior to that on the lower Choptank River and several other embayments (Eastern Bay, Patuxent R., Potomac R., Rappahannock R.) were reduced to a small fraction of their former size. When the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission finally moved in 2012 to institute a biologically realistic cap on the menhaden harvest, I had hopes that my lifetime studies of bird monitors such as Chesapeake loons and Connecticut River (Long Is. Sound) ospreys would demonstrate menhaden recovery. I am pleased to report: My 2014 observations of both species’ abundance say YES. For the first time in two decades, I tallied 400 loons on the calm afternoon of November 4, most of them in feeding flocks of 30 to 110 birds, on the Choptank River and Eastern Bay.

This is very good news for all of us who live along the East Coast: because, ecologically speaking, menhaden spin straw into gold. Our civilization drenches our coastal waters with nutrients. With adequate tidal flushing and oxygen, these are taken up by profuse plankton, the base of the food chain. Enter the menhaden: a filter-feeder in huge schools, which has a unique capacity to incorporate these plankton and pass them up the food chain. Which is also our food chain, because menhaden are prime prey for rockfish and bluefish. So this prey base recovery is a great boon for those who dine healthy, for commercial fishermen, and for sport fishermen. Consider all the economic and dietary benefits to society that go with those activities.

There is more: Menhaden are recycling our societal wastes—they provide unique Ecological Services for free in our coastal waters, if only we have sense enough not to greedily deplete them. Their regenerative capacity is evident, and it does allow local small-business harvest when properly managed and properly enforced. These fish are cash on the barrelhead, and again very useful to human food chains, this time as crab and lobster bait.

Certain birds at certain seasons provide a reading: a biomonitor that we are getting it right. So I am greatly encouraged by 400 loons! Of course, I will be looking and counting for the rest of November, before the loons follow the menhaden to Carolina waters. Ospreys, bald eagles, brown pelicans, and gannets also provide local seasonal Chesapeake wildlife spectacles that are fueled largely by menhaden.

Again, there is more: The late, great Canadian poet Stan Rogers sang of Newfoundland, “where the whales make free in the harbor.” But this summer, Humpback Whales were lunge-feeding in New York Harbor, with sprays of menhaden escaping from the sides of their great gaping mouths.

You must be logged in to post a comment.